WASHINGTON - Dr Henry Kissinger, the much-feted practitioner of unsentimental realpolitik who died in his home in Connecticut on Nov 29 at age 100, was different things to different people. To some, he was one of the great statesmen of the 20th century; to others, a modern Machiavelli; to admirers, an unsentimental realist; but to detractors, a war criminal.

Though his influence was greatest during the Cold War years of the 1970s, we live today in a world he helped to create, and to which he left a complex, deeply contradictory and conflicted legacy.

Henry Alfred Kissinger was born in 1923 in Furth, Germany, to middle-class parents. In 1938, the family fled their native country’s discrimination and anti-Semitism to settle in New York City.

He would rise in his adopted country to become National Security Adviser, Secretary of State, and thereafter eminence grise to a series of American presidents.

Shortly after the young Kissinger became a naturalised citizen, he was drafted into the United States Army and served as an intelligence officer in Europe during the war. On his return, he embarked on a distinguished academic career, receiving a bachelor’s degree from Harvard University in 1950, a master’s degree in 1952 and PhD in 1954 from the same university.

Dr Kissinger was appointed by President Richard Nixon to be his National Security Adviser in 1968, a post he held until 1975. In addition, he was also the 56th Secretary of State of the US, from 1973 to 1977. After he left the government, he founded Kissinger Associates, an international consulting firm.

To say Dr Kissinger loomed large over the world through the 1970s in particular would be an understatement.

Impact on Asia

In 1971, Dr Kissinger and President Nixon sent the nuclear-powered aircraft carrier USS Enterprise to the Bay of Bengal, ostensibly to help evacuate Western nationals from the war zone in the third Indo-Pakistani war. But really, it was a show of force to dissuade India’s Prime Minister Indira Gandhi from moving against West Pakistan.

The Indian army was already deep inside East Pakistan, liberating it from the genocide of the Pakistani army, which was crushing a Bengali nationalist movement in the eastern half of the country. Deaths in the conflict are estimated to have been upwards of 1.5 million; up to 10 million refugees fled to neighbouring India, with the city of Calcutta – now Kolkata – awash with emaciated refugees. The events were increasing pressure on Mrs Gandhi to act.

But the US backed West Pakistan. Mrs Gandhi turned to the Soviet Union to checkmate President Nixon with her August 1971 Friendship Treaty with Moscow, infuriating the duo in the White House.

But the US had its own reasons for its actions. Pakistan’s military dictator Yahya Khan was orchestrating Dr Kissinger’s historic 1971 trip to China – a trip that was to lay the ground for President Nixon’s visit to China in 1972. The US had had no diplomatic relations with China for more than two decades.

The US support for then West Pakistan during the war located in what became Bangladesh today is too often forgotten, except of course in Bangladesh.

“Nixon and Kissinger largely failed at sanitising their record on... Vietnam and Cambodia – but on Bangladesh, they proved to be remarkably deft at ducking public judgment,” wrote Princeton University professor of politics and international affairs Gary J. Bass in his 2013 book, The Blood Telegram.

Just two years later, when Dr Kissinger became Secretary of State, a Gallup poll found him to be the most admired man in America.

“Far from ending up a pariah, he remains a superstar, glistening as the single most famous and revered American foreign policy practitioner,” Prof Bass wrote.

Dr Kissinger is still seen as the guru of Washington’s foreign policy and national security establishment for the way he engineered a Sino-Soviet split, bringing China, under its pragmatic leaders Zhou Enlai and Deng Xiaoping, into the international community. It paved the way for the US’ eventual recognition on Jan 1, 1979, of the People’s Republic as the sole legitimate government of China.

Former top Singapore diplomat Kishore Mahbubani, currently a Distinguished Fellow at the Asia Research Institute of the National University of Singapore, has argued that the trip planted seeds which, with the help of personal relationships, ensured that the relationship between China and the US endured crises. The development was good for the region because as long as the US and China sustained a relatively harmonious relationship, Asean was not divided by their rivalry.

The bombing of Laos and Cambodia was another of Dr Kissinger’s most infamous chapters, alongside the blind eye to the genocide in Bangladesh (“Why would we give a damn about Bangladesh?” he once asked President Nixon).

The bombing was partly to destroy communist North Vietnam’s supply lines – including the storied Ho Chi Minh trail – and also to support the Royal Lao Government against the communist Pathet Lao.

As American casualties rose, tens of thousands of protesters took to the streets of US cities demanding an end to the war. That the bombing of Laos and Cambodia (and the invasion of the latter) was kept from the public led to huge blowback for President Nixon at home, culminating in the passage of the 1973 War Powers Resolution to limit the scope of the president’s ability to declare war without Congressional approval.

In 1975, Saigon in the south fell to the communist North, two years after a peace agreement between the North and South and the US was signed. Dr Kissinger was to claim a measure of credit for this, having played a critical role in the Jan 27, 1973 Paris Peace Accords, which – though he was widely seen as having betrayed South Vietnam – ended the war that had killed more than 55,000 Americans, many of them working-class draftees, and more than one million Vietnamese civilians.

Nobel Peace Prize

He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in December 1973. It was a controversial choice. The Nobel website says: “Christmas 1972 saw heavy bombing raids carried out over the North Vietnamese capital Hanoi by American B-52 bombers.

“All over the world, thousands of people took to the streets in protest. The man who ordered the bombing was at the same time spearheading ceasefire negotiations. The armistice took effect in January 1973, and the same autumn Henry Kissinger was awarded the Peace Prize together with his counterpart Le Duc Tho. The latter refused to accept the Prize, and for the first time in the history of the Peace Prize, two members left the Nobel Committee in protest.”

The North Vietnamese revolutionary general and diplomat who negotiated with Dr Kissinger, Le Duc Tho, rejected the Nobel Prize on grounds that real peace had not been established in Vietnam.

The bloody adventures in Indochina were ultimately futile. President Nixon and Dr Kissinger wanted to stop the perennial American bogey, communism, in Asia, but Vietnam and Laos are both communist today.

The carnage also led to the rise in Cambodia of the genocidal Khmer Rouge regime of the Maoist dictator Saloth Sar – better known as Pol Pot – which killed up to two million people. And in the heart of Laos today, farmers still find unexploded ordnance embedded in otherwise bucolic green crop land.

Role in South America, Africa

Asia was not the only arena that felt Dr Kissinger’s influence. Most notable of the Latin American interventions was the Sept 11, 1973, coup d’etat in Chile in which a group of military officers led by General Augusto Pinochet seized power, ending civilian rule.

Dr Kissinger persuaded President Nixon to greenlight the overthrow of the democratically elected Salvador Allende government, which they believed was turning Chile into a communist nation.

During the 17-year rule of Gen Pinochet, more than 3,000 people disappeared or were killed and some 38,000 became political prisoners and were tortured.

Records show that in 1976, Dr Kissinger overruled his aides on concerns over the regime’s human rights atrocities, telling Gen Pinochet: “We want to help, not undermine you. You did a great service to the West in overthrowing Allende.”

Dr Kissinger, however, also worked towards achieving detente with the Soviet Union, stewarding talks to reduce military spending, enhance stability, and establish bilateral discussions. The signing of the initial Strategic Arms Limitation Talks agreement in Moscow in 1972 was seen as a major achievement of the Nixon-Kissinger strategy of detente with the Soviet Union.

The US’ airlifting of military and civilian aid to Israel, in Dr Kissinger’s own words, “saved” Israel in 1973 when Egypt’s attack over the Jewish Yom Kippur holiday took Israel by surprise. Following the defeat of Egypt, Dr Kissinger’s shuttle diplomacy across the Middle East laid much of the groundwork for the 1978 settlement between Egypt and Israel, known as the Camp David Accords.

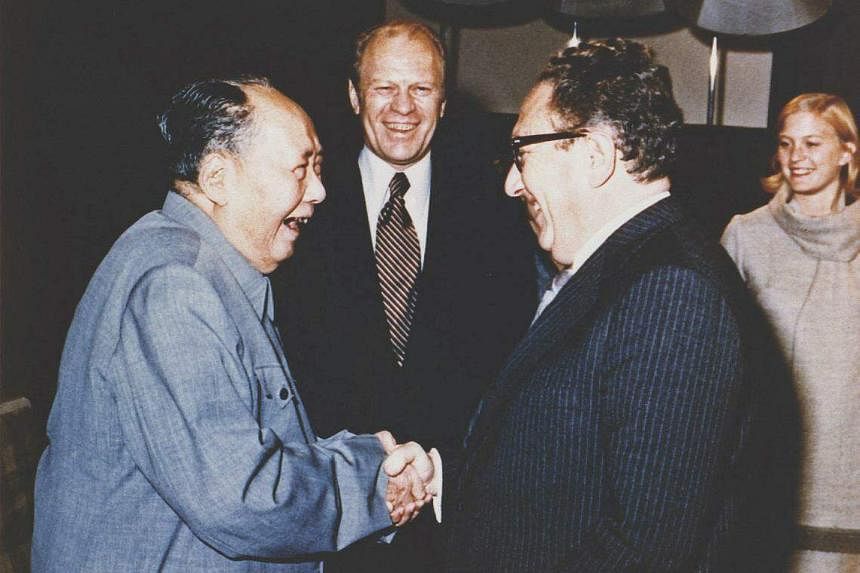

Diplomacy with China

But the defining feature of his diplomatic life was the breakthrough with China.

President Nixon and Dr Kissinger’s historic visit to the People’s Republic culminated in the Feb 27, 1972, Shanghai Communique, in which both countries pledged to work for “normalisation” of relations and to expand “people-to-people contacts” and trade opportunities.

Recalling it in July 2017 at the Harvard Club of New York City, Dr Kissinger told his one-time student and later friend, Harvard professor Graham Allison: “We felt we owed to the American people a demonstration that we had a notion of peace, that our purpose in life was not just to fight the Vietnam War, but to fit... Vietnam into a greater concept. And we thought a country of the magnitude and… history of China could not be excluded from any process that could be called peace.”

Fifty years after that momentous occasion, in July 2022, Dr Kissinger revisited Beijing to meet China’s President Xi Jinping. “The Chinese people never forget their old friends, and Sino-US relations will always be linked with the name of Henry Kissinger,” Mr Xi told him at the Diaoyutai State Guesthouse.

Dr Kissinger reportedly remarked: “Under the current circumstances, it is imperative to maintain the principles established by the Shanghai Communique, appreciate the utmost importance China attaches to the one-China principle, and move the relationship in a positive direction.”

Dr Kissinger’s zeal, continuing into his 10th decade, may be explained by his 2011 book On China (seen by critics as an attempt to burnish his controversial legacy, and in which he referred to Mao Zedong as a “philosopher king”).

In the book, Dr Kissinger, who wrote it at the age of 88, explained a fundamental characteristic of American foreign policy.

“American exceptionalism is missionary,” he wrote. “It holds that the United States has an obligation to spread its values to every part of the world.”

At his swearing-in as Secretary of State on Sept 22, 1973, he had said: “There is no country in the world where it is conceivable that a man of my origin could be standing here next to the President of the United States.”

Dr Kissinger’s parents, who had escaped Nazi Germany with their children, had watched his accession to the nation’s highest foreign policy office “as in a dream”, he said.

“They had been driven out of their native country; 13 members of our family had become victims of man’s prejudices. They could hardly believe that 35 years later, their son should have reached our nation’s highest appointive executive office.”

No other former secretary of state has maintained so intellectual a presence and influential a role for decades after leaving office, said Dr Robert Manning, distinguished senior fellow with the Reimagining US Grand Strategy project at the Stimson Centre in Washington. Every president since Richard Nixon – with the notable exception of Mr Joe Biden – solicited Dr Kissinger’s advice.

“His achievements as Secretary of State and National Security Adviser – China opening, 1973 Middle East war diplomacy, nuclear arms control and detente – are historic,” Dr Manning told The Straits Times.

“Yet one can also cite extending the Vietnam war causing thousands of deaths, the impact of his gunboat diplomacy in the Bay of Bengal and its impact on the war leading to Bangladesh’s creation, the 1973 Chile coup with which he did not cover himself in glory,” he said.

“But his longevity combined with his sustained intellectual output in books on China, diplomacy, world order, and artificial intelligence have made him a unique public figure.”

The phrase is often used too freely, but this time it is indeed appropriate: The demise of Dr Henry Alfred Kissinger does, in fact, mark the end of an era.