Could living things be drifting within the toxic atmospheric soup swirling around Venus? Astronomers say this is a possibility, after discovering a foul-smelling gas there that is an integral part of life as we know it.

Phosphine gas - made of phosphorus and three hydrogen atoms - is produced by microbial activity in environments such as mangroves, animal intestinal tracts and sewage. If not for living things, phosphine would not be naturally found on Earth as it cannot be made by any other atmospheric or geological process.

Work that led to the discovery of phosphine on Venus began more than two years ago.

In June 2017, Professor Jane Greaves - an astronomer at Cardiff University in Britain - and her team studied Venus through a powerful telescope, the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope in Hawaii. The telescope uses radio wavelengths to scan the planet, and phosphine was one of the molecules that absorbed the radio waves. The gas was discovered in Venus' atmosphere, 50km to 60km away from the surface.

The findings were confirmed and replicated in an array of telescopes on a plateau in Chile.

But scientists will not know for sure if a biological source is responsible for the phosphine without sending a spacecraft to Venus, which is what Rocket Lab, a private small-rocket company founded in New Zealand, has been working on, according to reports. The company says it has developed a small satellite that it hopes to launch on its electron rocket in two years.

The phosphine discovery was published in Nature Astronomy this week, and another paper was submitted to the journal Astrobiology.

The announcement sent ripples through the planetary community, casting the spotlight on a hostile planet long overlooked in the search for life beyond Earth.

Scientists say, however, that we cannot rule out the possibility that the gas is produced by some as-yet unknown process on the second planet from the Sun.

The high-pressure atmosphere on Venus, and temperatures reaching 460 deg C, mean that earthly creatures would be cooked and crushed almost immediately. Then there is the rain to contend with, which on that planet is made up of extremely corrosive sulphuric acid.

However, as early as 1967, renowned astronomer Carl Sagan and biophysicist Harold Morowitz had suggested that Venus' clouds could sustain life.

"If small amounts of minerals are stirred up to the clouds from the surface, it is by no means difficult to imagine an indigenous biology in the clouds of Venus," they wrote in a paper published in Nature.

Fifty years later, the researchers who discovered phosphine on the planet have cautiously laid the same idea on the table.

HYPOTHESIS OF LAST RESORT

"It was kind of a hypothesis of last resort," said Dr Sukrit Ranjan, postdoctoral fellow at the Centre for Interdisciplinary Exploration and Research in Astrophysics at Northwestern University in the United States, and one of the authors of the papers.

-

Traces of life in the cosmos

-

MARS

Though it is dry today, the red planet had oceans, rivers and lakes about four billion years ago. Ancient microbial organisms might have existed then, as the presence of water is a key indicator of the possibility of life.

Recently, a rover found organic material in sedimentary rocks on Gale Crater, which is an ancient lake bed.

Organic, carbon-based materials could indicate the existence of life forms.

-

EUROPA, JUPITER'S MOON

Scientists are almost certain that a massive ocean, probably holding twice as much water as Earth's oceans combined, flows beneath the Moon's icy shell.

The United States' National Aeronautics and Space Administration is planning a mission to Europa to find out if it is habitable.

-

EXOPLANET K2-18B

Far beyond our solar system at 110 light years away, a planet twice the size of Earth has been found to contain water.

But its strong gravity would make it difficult to walk upon.

Shabana Begum

"We have to be self-sceptical and very careful. Biology really needs to be the explanation of last resort because the atmosphere of Venus is a very harsh environment and it isn't a natural fit at least for life as we know it."

He and his team were over the moon when the discovery was confirmed. "Science often doesn't have very many of those 'gotcha' moments. These eureka moments are actually quite rare," he said.

He stressed that it is by no means certain that the finding definitely points to life on the planet, although there is no other way of explaining its presence.

"We're not proposing that there is biology on Venus. What we're saying is that the existing mechanisms that we have used to explain the presence of phosphine there have so far fallen short," he told The Straits Times.

Local experts ST spoke to also said it was too early to jump to conclusions.

"I think it is premature to consider (the presence of phosphine) as a sign of life. There is a lot we do not know about the atmosphere of Venus, such as the chemical reactions that would create phosphine, or even the source of phosphorus," said Dr Abel Yang, a lecturer at the National University of Singapore's (NUS) physics department.

Dr Ranjan added that the team had analysed possible processes that could produce phosphine, such as lightning, volcanic gas and meteoritic activity, but none of those could produce such high concentrations of the gas.

The amount of phosphine in Venus is about 20 parts per billion, which exceeds the amount that known processes can churn out, by several factors of 10.

That left the team with two options: an exotic chemical or geological mechanism that is unknown, or the more tantalising option - biological processes, which are known to release copious amounts of phosphine, at least on Earth.

EXTRAORDINARY LIFE FORMS

As the late Dr Sagan suggested, Venus' clouds have elements that make it potentially habitable.

For one thing, the area containing phosphine has liquid water, which is a main ingredient for life.

"At about 50km altitude, the atmosphere has roughly similar atmospheric pressure and temperature to Earth," said Dr Yang. "That, however, covers only the physical aspects and does not cover the chemistry aspect (of the environment)."

Dr Ranjan said the promise of water shrinks in comparison with the high amounts of sulphuric acid in the clouds, which create a harsh and hostile home. Sulphuric acid can dehydrate water.

"Any kind of life, if it's present there, would have to endure conditions that are much, much more extreme than anything we have here on Earth," he added.

"It's far out of the bounds of any of the extremophiles that we have here. So it would need to have some kind of really extraordinary (traits), if it's there."

Extremophiles are organisms on Earth that thrive in extreme environments such as deep ocean trenches and inside the Earth's crust.

The phosphine discovery is just the prologue of this new cosmic narrative, and Dr Ranjan views the papers more as a "call to action, as a call to further work, more than anything else".

He hopes that the scientific community will come forward to double-check the team's findings, unearth the chemistry of phosphine further, and even plan missions to Venus to take a closer look at its atmosphere.

"In order to rule out geological process as the cause of phosphine production, researchers need to consider more unknown geological processes in their modelling," stressed Dr Cindy Ng, a senior lecturer at NUS' physics department.

LIFE AS WE DON'T KNOW IT

All living things on Earth are made of carbon, the building block of life, but is there a possibility of non-carbon-based life forms elsewhere?

Scientists are often hesitant in speculating about this as they risk delving into the realms of science fiction.

But a recent study by three of the phosphine researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology analysed the possibility of silicon-based life, and posited that sulphuric acid could support more compounds with carbon-silicon bonds.

"The central question that lies behind this is whether there has been a second genesis for life anywhere other than on Earth," said Professor Stephen Pointing, director of science at Yale-NUS College, who has spent more than 20 years researching microbial life in extreme environments worldwide.

Former Science Centre Singapore chief executive Chew Tuan Chiong noted that looking for life forms similar to what is found on Earth satisfies "an innate curiosity and is also meaningful for existential reasons", although this may be far from reality.

"We are likely to be surprised and possibly shocked by what we eventually find," he said.

Dr Chew added that it is almost a certainty that there is life - whether it is in a form seen on Earth or something beyond our wildest imaginations - somewhere in the vast universe. The difficulty, however, lies in knowing what to look for.

"That's why we dream about finding extra-terrestrial intelligence in our image, or those which at least manifest themselves that way.

"In a sense, it is like searching for God."

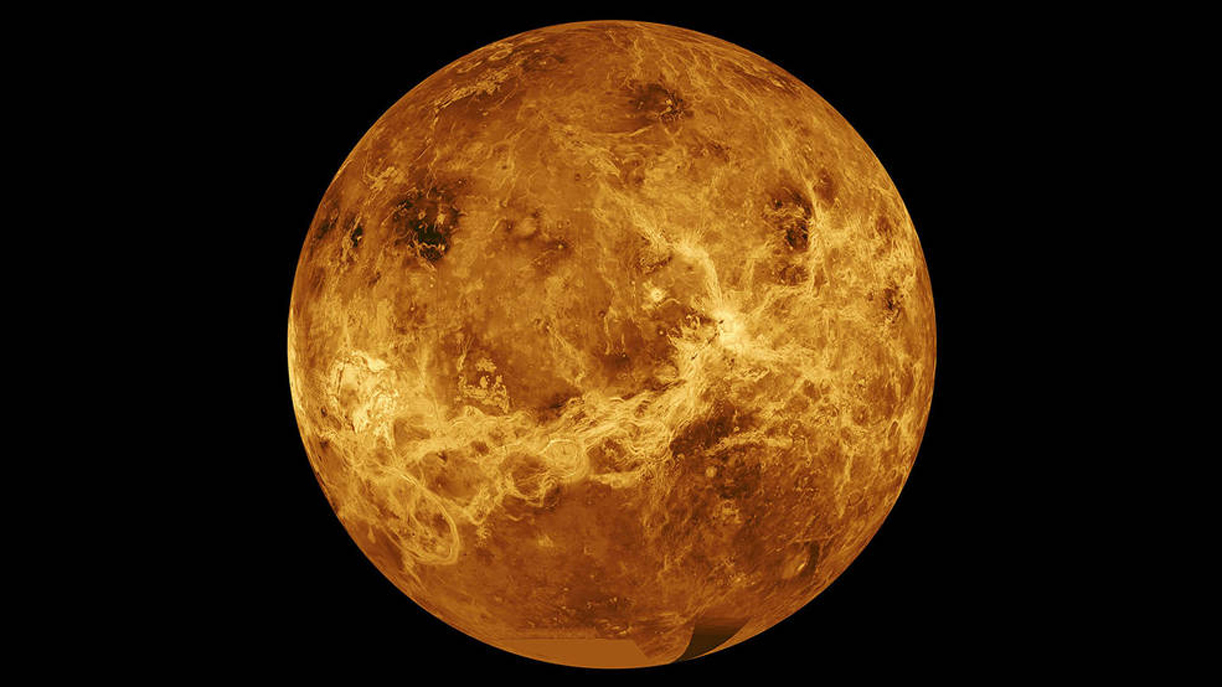

The fiery planet

Similar to Earth in size and mass, Venus is often described as Earth's sister. But the infernal orb and the blue planet could not be more different.

For one thing, the surface temperature of Venus is a smouldering 460 deg C, making the planet 30 times hotter than Earth.

It is shrouded by an atmosphere that is mostly made up of carbon dioxide and is 90 times thicker than Earth's own.

Climate models suggest that Venus may have had shallow oceans during its early years, but these eventually boiled away because of overpowering greenhouse gases.

It succumbed to severe global warming early, becoming the hell we now know.

But the planet is vicious and beautiful in equal measure.

Venus was named after the Roman goddess of love and beauty, and symbolises passion and romance.

Also known as the evening star, Venus is the second-brightest object in the night sky after the Moon.

Shabana Begum