To state that we live in a complex and challenging world would be a cliche, for the world has always been a complex place, and complexity is not about to disappear.

Notwithstanding the yearning for peace and quiet that some of us may harbour, or a retreat to a place of safe isolation, it should be admitted that no such place exists today.

Though we are assaulted daily by news of violence and turmoil, it is not as if the world has suddenly grown more unnerving: The causes of anxiety and irritation have always been present.

But the global communicative infrastructure that we have created, and which now binds the globe together, has brought complexity into our lives, to our living rooms, and even to our fingertips via smartphones, at a speed and on a scale unprecedented in modern history.

Societies that fail to adapt to change often find themselves at the back end of history. We are unable to reject new inventions like the Internet in the same way that we cannot live without electricity.

But living in a culturally complex world also means that we encounter differences in lifestyle, world views and ideologies on a daily basis.

The tragic killings at the office of Charlie Hebdo magazine in Paris last month demonstrated all too clearly that differences of interpretation and understanding are not merely subjective but can lead to real conflict as well - for one person's humour can be interpreted as insult by another.

Complexity shadows modern society as it evolves, and it will never leave us.

The extent to which societies can absorb and adapt to change is always open to question. This is because no society is made up of uniform beings, and not everyone has the same level of tolerance for change. In the face of change, some societies grow more open, while others regress and close themselves up to the world.

A quick look at online albums will show that Afghanistan's society was far more tolerant and laid- back in the 1950s than it is today; while the formerly closed societies of Eastern Europe now embrace change on a daily basis. This simply shows that societies do not develop in a linear manner, and there is no reason to believe a society that is tolerant and open will remain so indefinitely.

The cost of social inertia and unwillingness to adapt to new realities is also clear to see: When militants choose to bomb schools for girls on the basis of an outdated belief that women do not need or deserve education, they are in fact dooming not only the girls but the rest of society too.

Change - be it social, economic, political or cultural - will happen nonetheless, but perhaps what is needed is some means through which society can be prepared for it, and if magic pills don't exist then perhaps we can consider the role of art as an agent of change.

Art as an agent of change

HOW then do we develop social resilience in the face of unexpected contingency and new opportunity structures?

States grapple with this challenge daily for they are concerned with the need for development on the one hand and the need to equalise society on the other.

While the technocrats and securocrats debate over policies related to welfare and security, one group has been left out of the discussion altogether: artists and the producers of cultural capital.

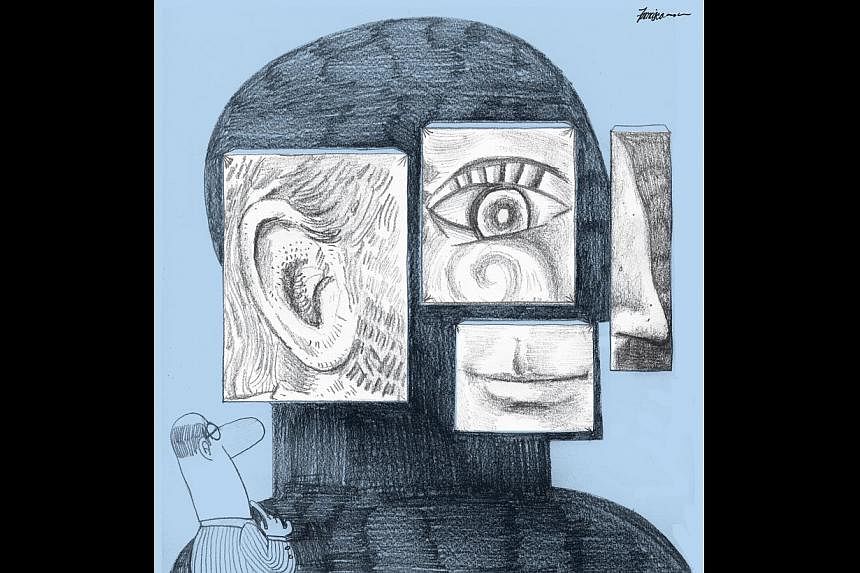

Art - and by this, I mean good art that is thought-provoking, enlightening and critical - can and does produce the intended effect of challenging our settled assumptions in no uncertain terms. Here, art should not be confused with things that are sweet and pretty - for art is not necessarily pretty (though it can be pleasing to the eye) and things that are only pretty ought to be regarded as decor rather than art.

Art's impact on society, and the manner in which it can change the way we see and respond to the world, is well recorded by now.

When James Joyce published his novel Ulysses, the work caused a stir among the reading public. It was evident that society was not ready for such a novel, which redefined the canon of literature and which is now regarded as one of the major works of Modernism of the 20th century.

Though it is now taught in most respectable literature departments, the initial reaction to the novel was one of shock and horror, leading to calls for it to be taken off the shelves.

The very fact that Ulysses is now considered one of the great works of English literature tells us something about how art and literature can push the boundaries of society and expand our horizons of possibility.

The same applies to the works of art - paintings, sculpture, statuary - that are found in galleries and museums the world over. Modern art was once vilified by the Fascists on the grounds that it disturbed their beliefs about the past and what an idealised traditional society ought to look like.

We should remember that in the 1930s, works of modern art were even dragged out of museums and burned in public by the extreme right-wing Fascists and Nazis who found them degenerate and decadent. The Soviets, too, destroyed works of modern art on similar grounds - that they challenged their ideological Utopia.

Confronting alternative realities

BUT art forces us to think, and to confront alternative realities that remind us of the ever-changing nature of the world around us.

The same holds true for classical art, such as the statues and artefacts in museums such as the Asian Civilisations Museum today: They tell us stories about our past, and remind us of the pre-modern era when South-east Asia was an inter-connected, fluid and porous region marked by movement, migration and external cultural influences.

These works of art are visual proof of the fact that borders are not natural but man-made, and that all the countries of the region - Singapore included - were part of a porous and fluid world once.

Classical works of South-east Asian literature like the Javanese text, the Serat Chantini, amaze us today with its frank discussion of spirituality and sexuality, and remind us that our ancestors were able to address such complex issues in times long gone.

What are these, if not the very tools that can be used to reawaken our understanding of the continuities across our region, and to prepare society for the age of globalisation that is already upon us?

Good art, which should be critical, thought-provoking and challenging, unsettles us. It provokes us in a way that makes us question and challenge ourselves and, in the process, it opens up new thought-structures that allow us to look again at the world.

In the light of current controversies and tensions worldwide, societies must learn to grapple with change and the sense of the other, or alterity.

Appreciating the role that art can play would be the first step in this learning process. It would mean that the trip to the museum or the gallery is no longer a happy jaunt to see some pretty things.

It also means that technocrats and policymakers have one additional means to help society build resilience in the long run, and suggests that social resilience is best achieved when the members of society decide to challenge themselves first.

The writer is associate professor at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University.