SINGAPORE – William Lim Siew Wai – one of the principal architects of modern Singapore – died on Jan 6, aged 90.

Although many Singaporeans know him as the creative force behind People’s Park Complex, Golden Mile Complex and other iconic buildings, an online memorial reveals a multifaceted man: loving husband, doting father, arts and heritage champion, and social activist.

The website on We Remember, a global genealogical platform by American company Ancestry.com, was set up by his family and has been active since Jan 7.

The memorial has entries from Mr Lim’s friends and urban collaborators, including architectural luminaries such as American architect and former classmate Frank Gehry, as well as Singaporean civil society activist Constance Singam.

Mr Gehry, 94, who attended Harvard University with Mr Lim from 1957 to 1958, wrote: “He was always the smartest guy in the room. I enjoyed the interactions immensely when we were students.”

Ms Singam, 87, wrote that Mr Lim had “dominated civil society activism” long before she came on the scene.

Meanwhile, the Nanyang Technological University Centre for Contemporary Art Singapore runs an online resource platform on its past exhibitions and public programmes. Part of this is an exhibition from 2016 to 2017 on cities for people, inspired by Mr Lim’s practice and the initiatives of the Asian Urban Lab he started with colleagues in 2003.

The centre’s first IdeasFest 2016/2017 festival featured projects that expand on some of Mr Lim’s ideas on sustainability and public spaces. The platform’s updates cover the third iteration of IdeasFest in February 2023, titled Food Eat. Secure. Sustain.

There was a common thread of “thinking out of the box” that ran through every aspect of Mr Lim’s life, according to his daughter Lim Chiwen and his son Lim Weiwen, both in their 50s, as they reminisce about their father at Weiwen’s double-storey apartment in Holland Road.

Behind the illustrious public figure, Mr William Lim carved out time from a punishing schedule to be with his family. Chiwen recalls how her father encouraged her, when she turned 18, to entertain her friends in the family apartment, which at the time was a penthouse in Golden Mile Complex with a well-stocked bar.

“I can clearly remember him saying, ‘Call your friends over and have a party here instead of elsewhere, and I will supply the booze,’” says Chiwen, who is married and a “professional mum” to her daughter and son, who are both in their 20s and studying abroad.

The idea was for Mr Lim to keep an eye on his daughter and her friends, and not have to worry about where they would end up in the wee hours.

“It was done in a casual, fun way, yet there was a lot of out-of-the-box parenting involved,” she adds.

Weiwen, a real-estate fund manager, recalls how their father would always make time for dinner with them and their mother Lena, despite his hectic schedule.

Mrs Lim, a former librarian, ran the bookstore and publisher Select Books for almost three decades before selling it in 2004 to spend more time with her family. She was also a founding member of women’s advocacy group Association of Women for Action and Research (now Aware) from 1985 to 1987.

“Sundays were sacred for us as a family,” says Weiwen, adding that the whole family would play squash in the mornings before heading to lunch with their paternal grandmother and other relatives.

“Our father was a great ‘connector’,” recalls Chiwen. “He often hosted dinner parties and talked about everything from architecture to politics.”

Weiwen says his father had a unique way of teaching money management and saving.

“When Chiwen and I were just in primary school, my father would take our Chinese New Year hongbao (red packets) and invest the money in stocks on our behalf,” he recounts.

“It made us scramble the next day to learn more about the firms he had invested in. It was not only a crash course in personal money management but also in making us think about saving instead of spending.”

At work, the senior Mr Lim’s “out-of-the-box” approach saw him teaming up with some of the most talented pioneer architects in the early days of nation-building in Singapore.

In 1967, he co-founded Design Partnership with fellow architects Koh Seow Chuan and Tay Kheng Soon.

Mr Tay, the principal designer of People’s Park Complex and Golden Mile Complex, left to set up his own practice in 1974, and Mr Lim and Mr Koh established DP Architects a year later. In 1981, Mr Lim also left DP Architects to found his own practice, William Lim Associates.

Mr Tay, now 82, went on to head a successful practice as the founder of Akitek Tenggara in Kuala Lumpur. He later became an adjunct professor at the School of Architecture in the National University of Singapore until 2021. He also authored Activist Architecture: Thoughts On Asian Architectural Education, which was published by Epigram Books in 2021.

Mr Koh, now 83, retired from DP Architects in 2019. The group is one of the largest architectural practices in the world today, with more than 900 employees in 11 countries.

He tells The Straits Times that the early years of Design Partnership were challenging yet rewarding.

“All the three founding partners truly worked as a team, exchanging ideas and participating in the design and concept of our major projects, such as People’s Park Complex and Woh Hup Complex (renamed Golden Mile Complex),” says Mr Koh, who is also a philatelist, art collector and philanthropist.

He says everyone at the firm “pooled and applied all the talent for the benefit of the projects at hand, as we were all committed and wanted to perform our best for the firm during the challenging times”.

“This teamwork yielded the best results, and laid the foundation for the firm and the role it played in nation-building and crafting a national identity.”

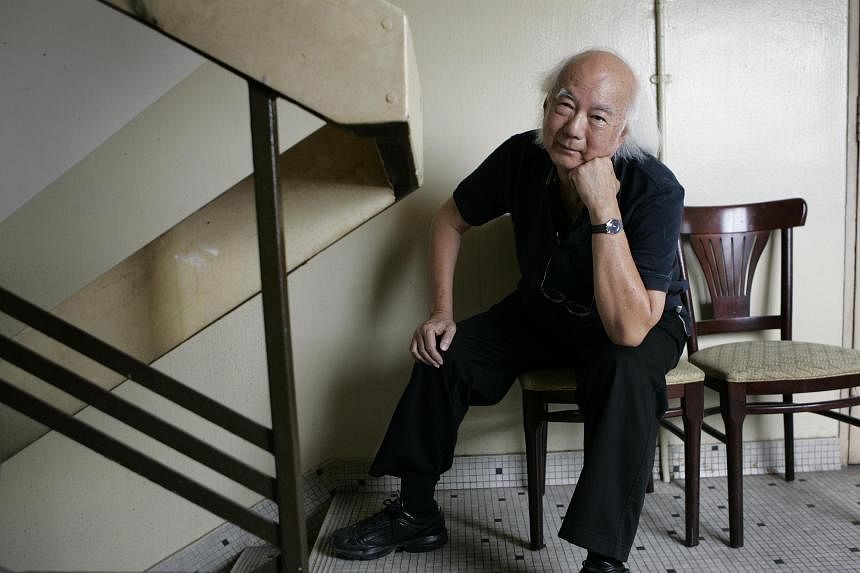

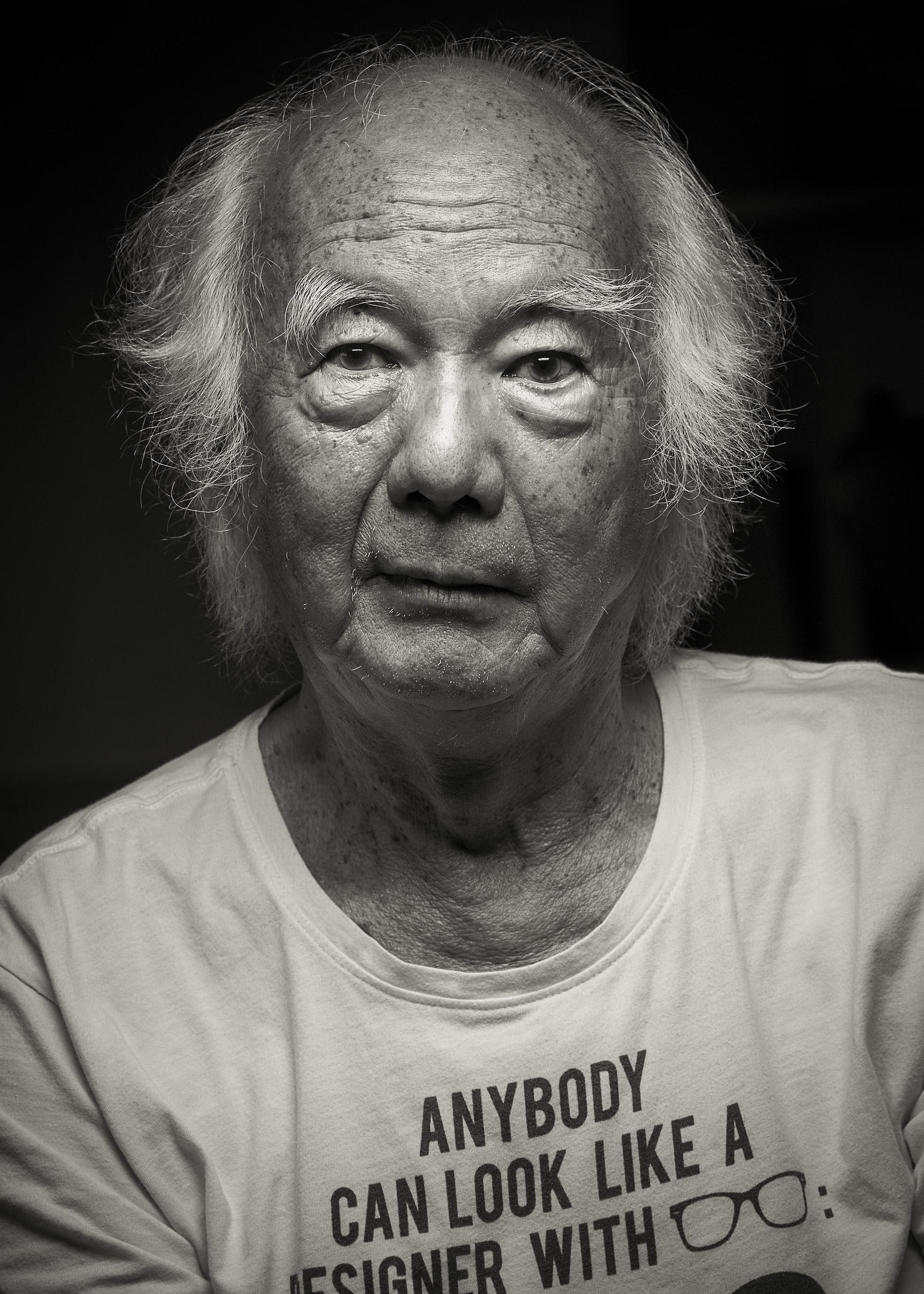

According to Mr Mok Wei Wei, Mr Lim’s protege and collaborator for 20 years, the celebrated architect was interested in much more than architecture. He describes his mentor as an urbanist “to the core”, spending most of his time thinking about the context of architecture within a city, including its social, cultural and economic aspects.

“In essence, William was an urban activist,” says Mr Mok, who is 66 and a multi-award-winning architect in his own right.

“In order to advance his urban advocacies such as conserving the historic settlements and shophouses in the 1980s, he became an ‘enabler’ who brought talented people together to collaborate on meaningful projects.”

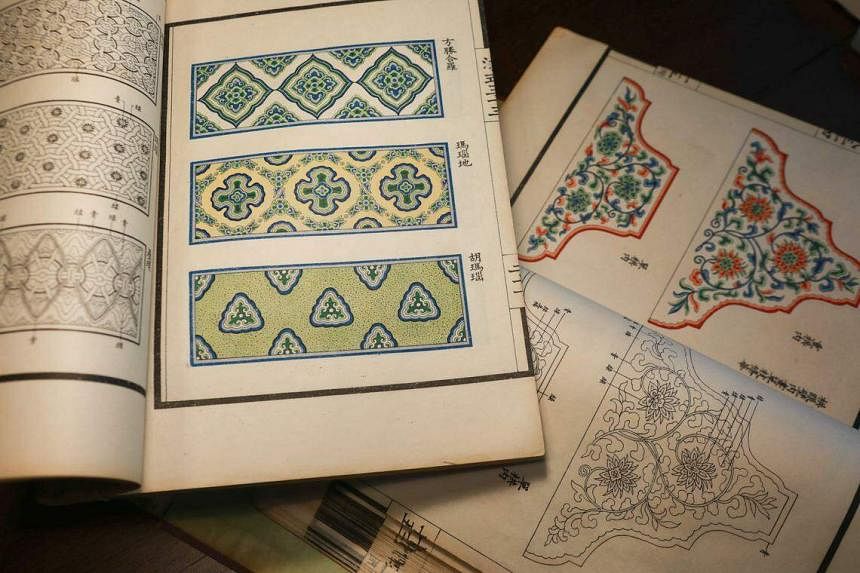

At his W Architects office in Henderson Road, Mr Mok pulls out a rare 1920s reprint of a book on Chinese timber architecture, which was a birthday gift from Mr Lim in 2011.

The Yingzao Fashi, also called the Treatise On Architectural Methods or State Building Standards, is a compilation of eight books written during the Song Dynasty and published in AD1100.

Mr Lim had received the compilation in the 1950s from his father, the late Mr Richard Lim Chuan Hoe, a lawyer and deputy speaker in then Chief Minister David Marshall’s Singapore Government. In a handwritten note in the book, Mr Lim says: “I hope you will find this document useful. My father gave it to me before my departure for AA (Architectural Association in London).”

Mr Mok recalls his mentor’s interest in observing people’s unique behavioural patterns and nuances as a result of cultural differences between the East and the West.

“The Western approach to problem-solving is very linear, meaning you tackle problems head-on from different angles till you can find a solution,” he says, recounting Mr Lim’s observation.

“But Eastern thinking is totally different. Just like the game of Go, William’s way is to encircle the challenge in order to come up with the best course of action that solves problems at all levels,” adds Mr Mok, referring to the ancient Chinese board game where two players place black and white “seeds” on a grid of 361 squares to encircle and capture territory in order to win.

This, he adds, has been at the crux of their shared value system in their 20 years of architectural collaborations.

For Mr Lim, the arts were just as important as urban theory and architecture. Mr Ivan Heng, founding artistic director of local professional theatre company Wild Rice, says the pioneer architect and his wife were avid supporters of the arts.

Mr Lim donated a “generous gift” to Wild Rice on his birthday in 2011, at a time when the theatre was going through a difficult time due to funding cuts, says Mr Heng, 60.

“His belief and support enabled the creation of new plays, and supported many home-grown writers, notably our resident playwright, Alfian Sa’at. Most importantly, it gave us the courage and confidence to press on,” recalls Mr Heng.

Later, in celebration of Mr Lim’s 90th birthday, the couple sponsored the installation of seats at Wild Rice’s new theatre at Funan mall in North Bridge Road.

Mr Heng says: “He understood theatre’s role in carving out a safe space to examine and reflect on the most challenging issues of the day. His respect and regard for artists reflected his patronage, which was generous and visionary in that it came with no strings attached.”

He adds that Mr Lim “challenged the orthodoxies of the times” and was a public intellectual. “William often brought together architects, designers, activists and artists to engage in dialogue and exchange ideas at events, as well as intimate salons in his home.”

Mr Ho Weng Hin, founding partner of architectural conservation specialist consultancy Studio Lapis, interned at William Lim Associates during his architecture school Year Out in 1998. The internship was an eye-opener in more ways than one, he recalls.

“I was part of the project team working on the Marine Parade Community Club,” says Mr Ho, who is also the Singapore Chapter founding chair of Docomomo International, a non-profit organisation dedicated to the documentation, advocacy and conservation of 20th-century heritage.

“A team of young and enthusiastic designers with varied aesthetic leanings took charge of different parts of the complex project. Like a skilful conductor, William guided this diverse team, giving each ample creative space while making sure each piece of the design would fall into place with aplomb. Frequent design reviews were held in the spirit of open-mindedness, transparency and trust such that everyone learnt from one another.”

In the late 1990s, Mr Lim was also actively involved in the Singapore Heritage Society, which he co-founded in 1987.

Mr Ho says he had the opportunity to observe monthly committee meetings in the office after work hours.

“It was inspiring to experience first-hand that an architect could also play the role of an urban activist, and fulfil a larger social and civic responsibility beyond the confines of conventional architectural practice.”

Info: Go to the online William Lim memorial at str.sg/ikTh, and read a compilation of his urban ideas by Nanyang Technological University’s Centre for Contemporary Art Singapore at str.sg/ikcJ

5 major designs by William Lim

In 1951, Mr Lim completed architectural studies at the Architectural Association in London, Britain’s oldest independent architecture school. After that, he went on a Fulbright scholarship to study city planning at Harvard University in the United States.

Some of his classmates include Pritzker Prize-winning architect Frank Gehry who, at 94, is still active in Los Angeles with a mega-project called the Grand LA Complex.

In Singapore, after a brief stint at Scottish design firm James Ferrie in 1957, Mr Lim set up Malayan Architects Co-Partnership in 1960 with Mr Lim Chong Keat and Mr Chen Voon Fee, whom he met while studying in Britain.

Datuk Seri Lim Chong Keat, now 93, designed modern landmarks in Singapore and Malaysia, such as the DBS Tower in Shenton Way (1975) and the Negeri Sembilan State Mosque in Seremban (1967).

Mr Chen, who died in 2008 aged 77, was also an author and a founder of Badan Warisan Malaysia, a Malaysian charity that promotes awareness of heritage and conservation.

Mr Lim then formed Design Partnership – which became today’s DP Architects – in 1967 with Mr Tay Kheng Soon and Mr Koh Seow Chuan after Singapore achieved independence in 1965.

In 1972, he was part of a team that designed the Modernist landmark, People’s Park Complex, which was the first of its kind in South-east Asia and inspired many future commercial developments. Woh Hup Complex was next in 1974 (the building was renamed Golden Mile Towers in the 1980s).

The architect founded William Lim Associates (WLA) in 1981 with Mr Carl Larson, who left the firm five years later in 1986.

Mr Mok Wei Wei, who joined the firm in 1982 fresh out of the National University of Singapore, became a partner of WLA in 1988. When Mr Lim retired in 2003, Mr Mok took on a new partner, Mr Ng Weng Pan, and renamed the firm W Architects.

According to Associate Professor Chang Jiat-Hwee from the Asia Research Institute and the Department of Architecture at the National University of Singapore, Mr Lim’s work was always on the cutting edge.

“William Lim left us an impressive range of buildings in different aesthetics and sensibilities that he had helped to plan and design in his long and productive career.”

Singapore Conference Hall and Trade Union House (1965)

The Singapore Conference Hall and Trade Union House in Shenton Way, now called Singapore Conference Hall, was designed principally by Mr Lim Chong Keat of Malayan Architects Co-Partnership. He worked closely with co-founders William Lim and Chen Voon Fee on what is now a national monument and one of Singapore’s earliest Modernist landmarks.

The firm had won a competition in 1962 to design the government building, which was both a conference hall and a trade union house.

Mr Tay Kheng Soon said in a 2001 issue of the Singapore Architect online magazine, published by the Singapore Institute of Architects, that the building was “an innovative attempt at evolving a modern tropical design language that has not been matched since”.

People’s Park Complex (1973)

The post-Independence building is listed as “threatened” by Docomomo Singapore, a non-profit global organisation dedicated to the documentation and conservation of buildings, sites and neighbourhoods of the Modern movement.

Fortunately, there has been no word yet on any plans to tear down the mixed-use landmark, which stands at 25 storeys tall and is one of Singapore’s best examples of Brutalist architecture.

Brutalist (or “Heroic”) design is an architectural style that came about in the 1950s, characterised by bare-bones construction that uses raw concrete in sculptural, angular shapes that feature steel and glass.

Mr Lim says that the absence of an anchor tenant in the two podium blocks’ layout of shops meant the spotlight was on the “little guys who mattered”, referring to fledgling small businesses.

The building’s internal circulation was designed for this, featuring many entrances leading to corridors of different sizes organised around stepped atriums.

Woh Hup Complex (1973)

Another project by Design Partnership was the Woh Hup Complex development (renamed Golden Mile Complex in the 1980s).

The architects adapted Brutalist architecture to a tropical context featuring “terraced” floor slabs, slanted beams, towering columns and “floating” staggered staircases, which demanded advanced construction methods in the late 1960s to early 1970s.

The 16-storey mixed-use strata-titled (privately held) building was also an example of a “vertical city” where residents could live, work and play – one of the earliest such designs in Singapore.

According to Prof Chang Jiat-Hwee of the National University of Singapore, Mr Lim worked with colleagues Mr Tay Kheng Soon and Mr Gan Eng Oon to design a form which provided a large semi-sheltered terrace above the offices and shops of the podium.

On Oct 22, 2021, Golden Mile Complex was gazetted a conserved building by the Urban Redevelopment Authority, making it the first large-scale strata-titled property to be conserved.

Reuters House (1990)

Mr Lim’s Reuters House in Ridout Road is a Postmodern design that showcases contemporary vernacular architecture.

The global information, news and technology group had bought the house for its Asia-Pacific managing directors in 1948, but it deteriorated over the years.

After a 1987 building survey, it was torn down and rebuilt by William Lim Associates into an elegant tropical residence.

Its two-storey square front block, linked to a single-storey rectangular rear block, may look like a typical colonial-era bungalow – but the inclusion of imposing timber columns, a pavilion-style roof and a courtyard add dimension to the design.

Mr Lim has said in previous reports that the Reuters House has a “yin and yang” quality, marrying traditional and modern concepts.

It later became the basis of what Mr Lim and his co-author Tan Hock Beng called “contemporary vernacular” in the 1998 book, The New Asian Architecture: Vernacular Traditions And Contemporary Style.

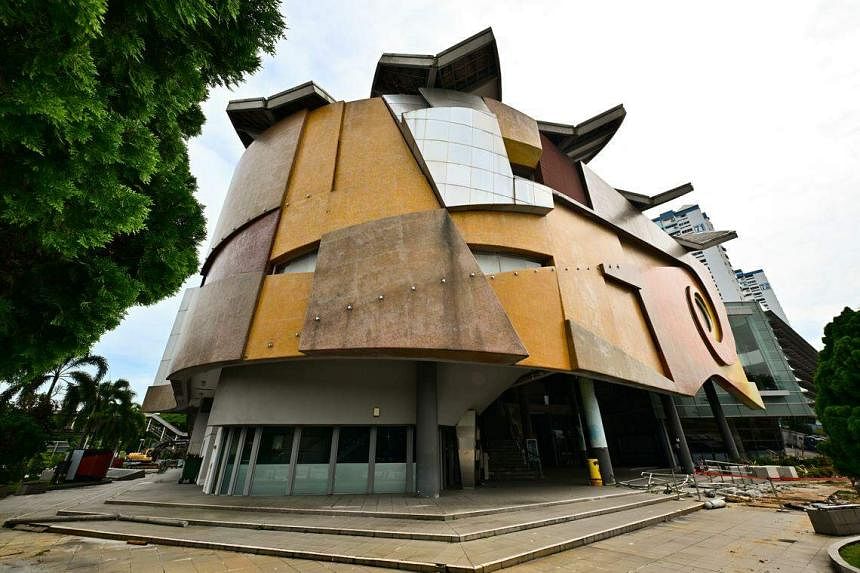

Marine Parade Community Building (1999)

The Marine Parade Community Building (MPCB) in Marine Parade Road, completed in 1999 as part of the landmark Community Centre Co-Location programme, was initiated by then Prime Minister and Member of Parliament for Marine Parade Goh Chok Tong, and designed by William Lim Associates.

The building was the earliest to feature an integration of amenities – a community centre, library and non-profit theatre company The Necessary Stage – within a single building to maximise land use.

The design team included architect Goh Kasan, the son of post-Independence poet and novelist Goh Poh Seng.

The mosaic mural in the central facade is the building’s most distinctive feature, called The Texturefulness Of Life by Thai architect Surachai Yeamsiri.

Measuring 63m by 12m, it is one of the largest public works of art in Singapore. It was fabricated by skilled artisans using lightweight concrete panels to create the geometric shapes.

In April 2022, it was announced that the MPCB would be demolished, with the People’s Association citing maintenance issues and a planned underground connection to an upcoming MRT station as driving factors.