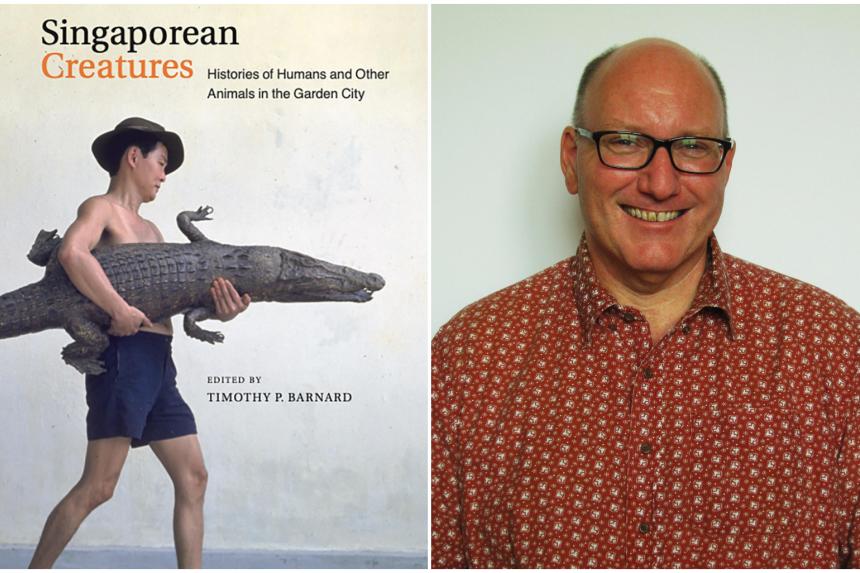

Singaporean Creatures: Histories Of Humans And Other Animals In The Garden City

Edited by Timothy P. Barnard

Non-fiction/NUS Press/Paperback/277 pages/Amazon SG (amzn.to/3w7i9VD)

4 stars

What claims do animals – say, the Zouk otters of social media fame, the feared and dengue-carrying mosquito Aedes aegypti or Singapore’s most iconic orang utan Ah Meng – have to being Singaporean?

Surely not by dint of legal citizenship or self-identification, but perhaps by the status Singapore’s human denizens and policymakers have bestowed on these creatures.

One might recall Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong’s words in 2018 upon the death of Inuka, the first polar bear born in the tropics at the Singapore Zoo: “He was as Singaporean as any of us.”

A new volume of essays on environmental history furnishes a lively and persuasive account of Singapore’s relationship with animals from the mid-20th century onwards. It follows the fate and agency of creatures like the crocodile from the final years of British colonial rule to Singapore’s nascent independence up to the present.

Edited by Timothy P. Barnard, associate professor in the department of history at the National University of Singapore (NUS), Singaporean Creatures does not explicitly argue for the peculiar – even provocative – moniker it uses as its title.

In his introduction, Barnard settles for the Singaporean Creature’s “complex role and position in Singaporean society and history”, but is cautious not to venture a restrictive definition tied solely to ideas of governance and control.

Readers, therefore, are free to draw conclusions from the collection’s eight wide-ranging essays – written mostly by historians – which implicitly argue for a term that at once implies citizenship, ownership, belonging and affinity.

For a “preliminary investigation”, the scholarly book certainly throws up several interesting conjectures and its fascinating narration of ideas will keep even the layman reader riveted.

One idea of the Singaporean Creature that runs throughout the book is how early national development policy regulated and structured Singapore’s relationship with animals. Unsurprisingly, the history of relocating citizens from kampungs to high-rise public housing from the 1960s onwards crops up frequently.

Mr Esmond Chuah Meng Soh, a graduate student at the Nanyang Technological University, shows how many Singaporeans who historically cohabitated with crocodiles had an attitude of “informed nonchalance” towards the reptiles.

This gave way to the transformation of crocodiles into symbols of “untamed nature” from the 1960s, as crocodile sightings became the subject of media sensationalism and even a form of cryptozoology with the fascination around white crocodiles.

His point resonates with an essay by Barnard, who argues how rhetoric around the belligerent presence of Aedes mosquitoes in post-war Singapore coincided with a rhetoric for the push for societal transformation through HDB flats.

It was also in 1968 when the Destruction of Disease-Bearing Insects Act was drafted, which provided more teeth to control persons who propagated a range of pests.

Assistant professor at NUS Faizah Zakaria contributes a substantial chapter on songbirds and how they line up with the emergence of a more manicured Garden City concept. The first formal bird-singing contest in Singapore, for example, was staged in 1964 – a much more pleasant alternative to bird fights such as cockfighting, which the Government was trying to outlaw then.

The binary of native and invasive species – or domestic and migrant species, to use terms associated with the human – also frequently emerges in the discussion. Both groups have claim to “Singaporean” status in a highly globalised, multi-species city – although this is not without controversy.

Assistant professor Anthony Medrano at Yale-NUS College makes the case for the common tilapia as a “diasporic fish”. It was a non-native species which came to Singapore through imperial Japan’s colonial network in Indonesia, which eventually became a forgotten chapter of Singapore’s role in the expansion of global aquaculture.

But the fate of the Singaporean Creature is not just the result of imperial ambition or social and economic imperatives. It is as much shaped by public fascination and fantasy: Facebook groups tracking the movement of otters, breakfast with Ah Meng and controversies around Inuka the polar bear are all part of that story.

One wonders, then, if the muted public reaction to the death of four gorillas within a year at the Singapore Zoological Gardens in 1983 – as cited by graduate fellow at the University of Hawai’i Choo Ruizhi – despite an international outcry meant that the gorilla had not qualified, at least in the public eye, as a Singaporean Creature.

Thoroughly intriguing and readable, Singaporean Creatures is also a worthy “sequel” to Barnard’s earlier book Imperial Creatures, which explored Singapore’s relationship with other animals within an earlier time frame of 1819 to 1942.

For readers who have been enthralled by a rare sambar deer sighting or horrified by the large crocodiles which still appear amid urban life, Singaporean Creatures reveals the historical sources of one’s fear and fascination.

If you like this, read: Eating Chilli Crab In The Anthropocene: Environmental Perspectives On Life In Singapore (Ethos Books, 2020, $11.90, Amazon SG, go to amzn.to/3vLyEa0), a series of essays on the environment through a more popular culture and often personal lens. There are discussions on Tiger Beer, orang minyak (“oily man” in Malay) films and the Singaporean pastime of eating crabs.