KAMALKOTE, KASHMIR (NYTIMES) - On Friday morning (March 1), Mr Mohammed Reyaz Khan, a farmer in the disputed region of Kashmir, crawled out of a bunker in his village and went to check on his sheep.

As he was walking, a mortar shell exploded nearby and a chunk of shrapnel ripped through his leg.

Scrambling to get him help, his family ran down a hillside carrying him on their shoulders, his lower body soaked in blood, a piece of white bone poking out.

"Our lives depend on the mood of the soldiers," said his cousin Muneer Ahmad Khan. "We will always live in fear."

In the decades-old enmity between India and Pakistan, one place almost always suffers: Kashmir, the beautiful but cursed Himalayan valley that both nations claim.

It happened again this week, as tensions between the countries exploded. Warplanes screeched across the sky dropping bombs, and thousands of soldiers mobilised in Kashmir, bringing the two countries to red alert.

Things were calmer on Friday, despite the shelling at the border and the suffering of people like Mr Mohammed Reyaz Khan.

Pakistan's Prime Minister Imran Khan called the pilot's release a goodwill gesture, and with the United States, China, Russia and many other countries urging both sides to de-escalate the crisis, India - though somewhat humiliated - seemed willing to pause.

Pakistani officials brought the pilot, Wing Commander Abhinandan Varthaman, to the Wagah border crossing in northwestern India, where hundreds of people had gathered to receive him.

Wagah had turned into a blur of orange, green and white Indian flags, and many people wore patriotic gear.

One man's baseball cap read in large block letters: "I LOVE MY INDIA."

Strong jingoistic currents have swept across India since Tuesday, when the air force sent warplanes into Pakistan to bomb what the Indian government said was a terrorist training camp.

India has long accused Pakistan of supporting Kashmiri separatist groups, and the air strike was in response to a Kashmiri suicide bomber's attack on an Indian military convoy, which killed more than 40 troops. It was the most devastating attack in Kashmir in decades.

Pakistan, which denies any connection to the Kashmiri militants, struck back on Wednesday, downing the Indian fighter jet. Both countries have nuclear arms, and the spiralling crisis put the entire region on edge.

But by Friday, Western diplomats in New Delhi, who have been holding countless meetings and working to defuse tensions, seemed much more relaxed. Their hopeful refrain was: The worst is over.

Several diplomats said that India's Prime Minister, Mr Narendra Modi, would look like the aggressor at this point if India staged more strikes, and that Mr Imran Khan had no incentive to push things further.

Mr Khan's priority has been to revive Pakistan's listing economy, and so far he seemed to have won this case in the court of world opinion.

His forces had captured an Indian fighter pilot, the pride of India's military. And his calls for restraint and peace, even if driven by self-interest, seemed to play well around the world, even in India.

"Whatever Pakistan's role has been in the Kashmir conflict, Imran Khan, the prime minister of Pakistan, has acted with dignity and rectitude," leftist Indian author Arundhati Roy wrote in an opinion piece published in HuffPost.

As for Mr Modi, she called his actions "unforgivable", alluding to the always-present possibility of a nuclear conflict between the states.

"He has jeopardised the lives of more than a billion people and brought the war in Kashmir to the doorsteps of ordinary Indians," Ms Roy wrote.

Many Indians, though, are sticking by Mr Modi.

In recent days, several Indians said in interviews that they believed his government's claims that the initial strike on Tuesday had been a success, and that Indian forces had vanquished hundreds of dangerous terrorists. So far, India has offered no proof of that.

Instead, reports from the rural area in Pakistan where the bombs fell cast doubt on the Indian claims.

Witnesses said that the bombs fell in a mostly empty forest and that the only person hurt was a 62-year-old villager who suffered a small cut above his eye.

"What terrorists can you see here?" he asked, according to Reuters.

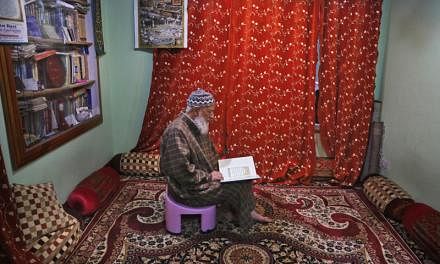

In Kashmir, people don't know what to believe.

Every evening, those who live along the disputed border, known as the Line of Control, cram into small, cave-like bunkers, overwhelmed by the bitter winter chill and the very real possibility of sudden death.

In the morning, they crawl out to gauge the destruction caused by the machine guns and artillery that are fired regularly during the night.

Even before this crisis, Pakistani and Indian troops constantly shelled each other across the Line of Control.

There are tens of thousands of troops dug in, facing each other. The rationale almost always given is that the other side started it.

Many times the artillery or mortar shells sail over the soldiers and land in villages, maiming or killing civilians.

Still, for centuries, Kashmir has been renowned for its beauty. It stretches between high white Himalayan peaks, and in the summer, the meadows are carpeted with wildflowers. In the winter, there is excellent skiing.

But Kashmir is a depressed place, with little development, few good jobs and a sense of hopelessness. It has been down for decades, ever since its people began chafing for independence.

Most of the area is controlled by India, a smaller slice by Pakistan, and a small but dogged insurgency has been fighting against Indian rule.

Religion partly fuels the divide: Kashmir is predominantly Muslim, like Pakistan; India is overwhelmingly Hindu.

Western officials say that Pakistani intelligence services used to work closely with the Kashmiri militants, and that several of the armed groups still receive money, weapons and expertise from across the border in Pakistan.

Life on the India side is often disrupted by militant attacks, street protests or government crackdowns.

Soldiers are everywhere: on the roads, in the apple orchards, standing with their guns behind giant coils of barbed wire.

Schools shut down frequently. So do stores, roads and the cellphone network.

Some young Kashmiris call their homeland "the world's most beautiful prison".

The Kashmiris who get out are often discriminated against. After the Indian convoy was hit in mid-February, hundreds of Kashmiri college students at universities in India were chased off their campuses. Many were terrified; some were beaten up.

Even in New Delhi, the capital, where many people from different parts of India live, some Kashmiris were thrown out by their landlords for one reason: They were Kashmiri.

"Whenever India and Pakistan fight, we are the first ones to suffer," said Mr Khan, the cousin of the wounded farmer.

Kashmir University political science professor Aijaz Ashraf Wani said Kashmir had become the major source of tension between India and Pakistan.

"We are the grass that suffers in the fight between two elephants," Prof Wani said.

"But," he added, "we are also the biggest reason these two elephants are fighting."