As if the pandemic itself were not enough, in Australia Covid-19 has sparked a major foreign policy crisis.

Over the past few weeks, just as the coronavirus itself has apparently been brought under control there, Australia's two most important relationships have spun out of control, leaving Australians wondering where they stand. This may well mark something of a turning point in the way this country sees its place in the world.

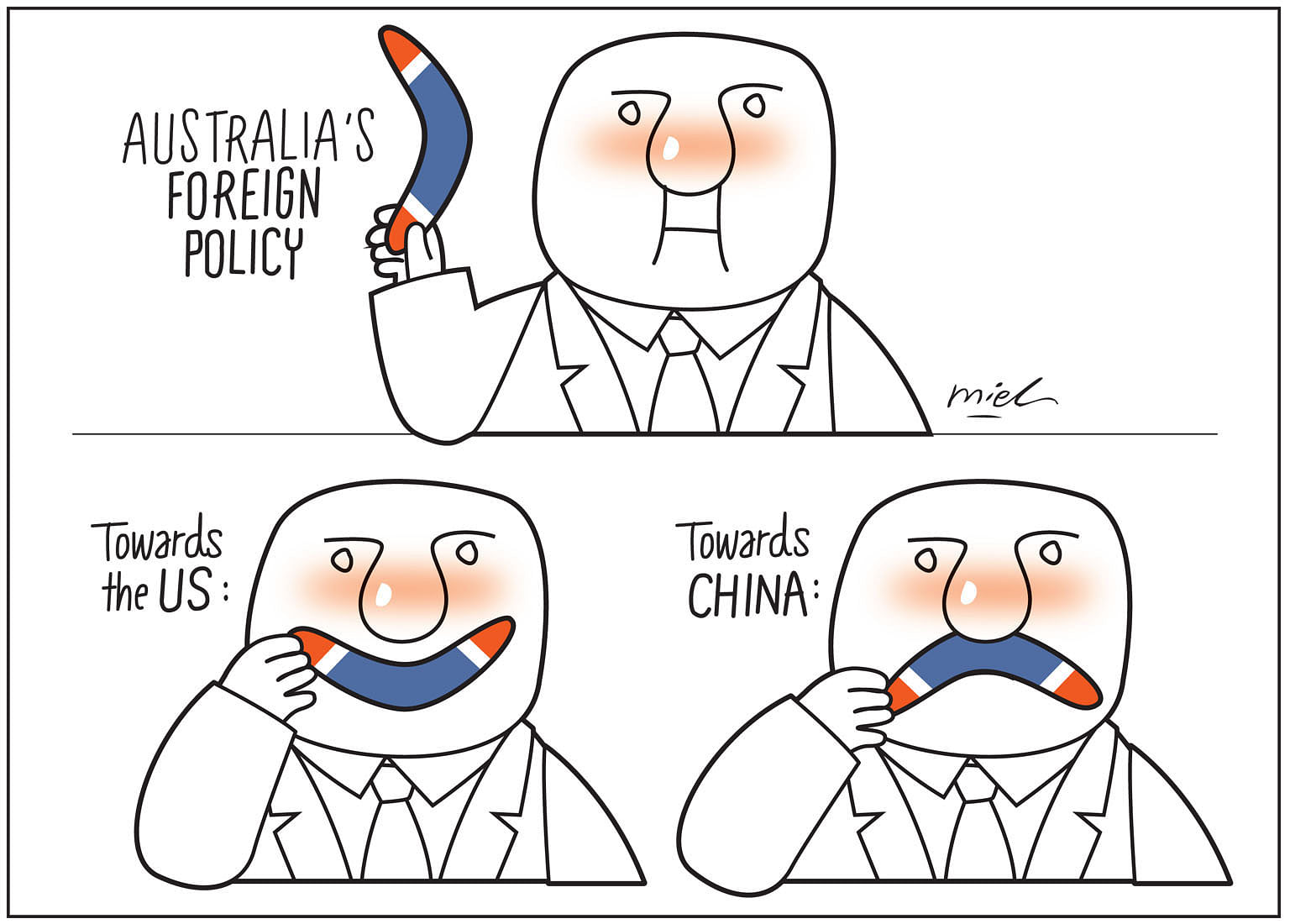

It is an uncomfortable feeling for a country which until now has dismissed concerns about Asia's massive strategic changes with breezy assurances that it will never have to choose between America and China. For 25 years, Australians have lazily assumed that they can depend indefinitely on China to make them rich and still rely on the US to keep them safe - and especially, safe from China.

But now the pandemic has starkly revealed the cracks in this carapace of complacency, and exposed dilemmas which will remain long after the lockdowns have passed. On the one hand, it has highlighted the fragility of Australia's ally. On the other, it has offered a frightening portent of the costs and risks of Australia's economic dependence on China.

Start with the United States. Australians were as surprised as anyone when Mr Donald Trump became President, but their underlying faith in America's power and purpose was not shaken. The pandemic has changed that. Mr Trump's absurd conduct during the crisis has shown his unfitness for office more vividly than ever before, and the disastrous impact of the coronavirus across the US has undermined confidence in its institutions and systems more broadly.

Above all, Washington's failure to provide leadership for the global response to Covid-19 has shown how mistaken it has been to rely on America to uphold the "rules-based order" that Australia has taken for granted. Instead, President Trump and his most senior officials seemed more interested in domestic political point-scoring than international leadership.

They have been trying to distract Americans' attention from the administration's mishandling of the crisis by making provocative allegations about the origins of the coronavirus and China's responsibility for the pandemic. Their aim has been to fan anger towards Beijing rather than to maximise cooperation when it is needed most.

All this has contributed to a seemingly irreversible escalation in tensions between Washington and Beijing which now makes it hard to imagine how a real Cold War between them can be avoided. At the same time, it is becoming less and less clear that the US has the economic weight, military power, political will or international standing to prevail in the bitter contest it seems so eager to help provoke.

MORRISON'S MISCALCULATION

This makes it all the more surprising that, earlier this month, Australia's Prime Minister Scott Morrison chose to echo some of Washington's more inflammatory language when he called for the establishment of an independent international inquiry into the origins of the pandemic.

The proposal itself is perfectly sensible, and something like it has now been adopted by the World Health Organisation (WHO). But in presenting his initiative, Mr Morrison seemed to endorse Washington's suggestions that Beijing was culpable in concealing the outbreak. He even went so far as to suggest that investigators should be given the same kind of powers as United Nations weapons inspectors, which risked implying that China was in some way comparable with a rogue state like Saddam Hussein's Iraq.

This was an obvious blunder.

It made no sense to propose an inquiry which could proceed only with China's concurrence on terms which Beijing was sure to oppose.

Mr Morrison's reasons for doing so remain unclear. One reason might have been to please Washington by echoing its accusations. But Mr Morrison has hitherto been careful not to follow the Trump administration's more inflammatory rhetoric against China, and Canberra has also gone out of its way to distance itself from Washington's accusation that the virus was created in a Wuhan laboratory.

So perhaps the explanation lies in domestic politics. Mr Morrison's four predecessors were all deposed by their own party, so no prime minster can take the loyalty of his or her followers for granted. Mr Morrison faces pressure from the right wing of his party, which has been calling for tougher responses to China's growing power and influence, and similar concerns have been raised by others both inside and outside Parliament. Mr Morrison may have decided that the fervid atmospherics of the pandemic provided an opportunity to pander to their demands by talking tough on China without fear of retaliation from Beijing.

CHINESE FURY

If so, he miscalculated badly. Beijing has responded furiously, mocking his proposal, and unleashing abuse in the Chinese press. The editor of the outspokenly nationalist Global Times went so far as to say that "Australia is always there, making trouble. It is a bit like chewing gum stuck on the sole of China's shoes. Sometimes you have to find a stone to rub it off."

More importantly, China's Ambassador to Canberra issued blunt threats of retaliation against Australia's all-important export markets in China. Those threats materialised this week when Beijing used a long-simmering trade dispute to impose crippling tariffs on Australian barley exports to China - and many are worried that worse may follow.

Not surprisingly, Australians responded angrily to this blatant bullying by China. Mr Morrison has refused to back down, saying that Australia's values and sovereignty are at stake, and he has been widely supported, including by the opposition Labor Party.

But other voices have urged caution. Business leaders and state governments have reminded Canberra that Australia can hardly afford to pick a fight with its most important trading partner by far at a time when the economy has been severely hit by the pandemic.

Their concerns are understandable. The political relationship, which has been frosty since 2017, has reached its lowest point since diplomatic contact was established in 1972. Nonetheless, China's share of Australia's exports has continued to grow. It now takes 38 per cent of everything Australia sells overseas - more than the next four major markets combined.

HARSH REALITIES

Given China's record of using economic coercion for political ends, it is hard to see how Australia can escape further punishment. And given the centrality of the China market to Australia's economy, it is hard to see how this will not inflict major damage on an economy struggling with the consequences of the pandemic.

Mr Morrison has said Australia must show patience. Perhaps he believes that Beijing will forget its anger once the pandemic is past.

If so, he is badly misjudging the situation yet again, because Beijing's tantrum is about a lot more than Covid-19. It is about its determination to take America's place as the leading power in East Asia. It is making an example of Australia. It wants to show that countries siding with Washington against Beijing will face heavy punishment, from which the US is powerless to protect them.

This is the hard reality of the new power equilibrium in Asia. Behind Mr Morrison's morale-boosting talk of values and sovereignty lies the simple fact that China today can impose heavy costs on Australia any time it likes, at low cost to itself.

And there seems very little that the US, even with a less flawed president, can do to stop it.

WHAT ARE THE ALTERNATIVES?

So what can Australia do? Some people talk of diversifying export markets to reduce China's leverage, which makes sense as far as it goes. But what other market is there for a million tonnes of iron ore a day? No other country offers anything like China's opportunities, so lower dependence on China means a smaller economy. What price, then, is Australia really willing to pay for those values Mr Morrison keeps talking about?

Another idea is for Australia to align with other countries, especially other middle powers, to present a united front against Chinese coercion. This too makes sense as far as it goes. But how realistic is it to expect other middle powers to endanger their own relations with Beijing to help Australia, or vice versa? Vague talk of a new "middle power" foreign policy is no substitute for the assurance which used to be provided by Australia's alliance with the US.

So thanks to Covid-19, Australia now faces the test which has always been waiting for it, ever since Europeans first settled in the country in 1788. How to sustain this country once it can no longer depend on Western powers to shield it from its powerful Asian neighbours?

• Hugh White is emeritus professor of strategic studies at the Australian National University in Canberra.